Jackson Pollock’s No. 32 – A Symphony of Spontaneity

October 2019

A sunny Friday afternoon in October. There are engagements waiting, there is somewhere else to be. And anyway, it was supposed to be just a quick stop, a check-in really. Yet, here I stand on the first floor of the K20 museum, mesmerized, transfixed, transcended, unable to tear myself away, slowly drifting out of the estuary of time on a gondola of color and shape.

Downstairs, visitors are queuing to see Ai Weiwei’s accurate pile of sunflower seeds and carefully arranged images made of LEGO bricks. Clusters of high school students on foyer benches are sharing their impressions with the world by way of their smartphones, a world that has pretty much made real life interaction with art, with each other, with one’s self redundant. The upstairs is quiet in comparison. Here, the noise of the marble hall fades away, making room for a different sound – that of my own heartbeat.

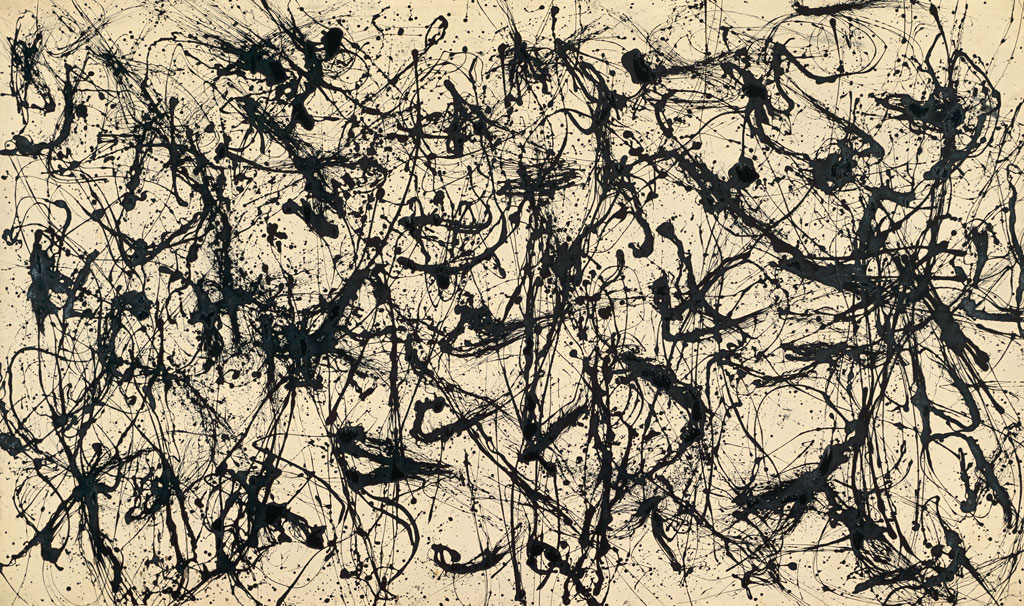

Leaving behind Ai Weiwei’s rusty iron bars in wooden caskets, I open the door to a much more spontaneous but no less profound perception of art: Paradigmatic in its artistic zeitgeist, way more radical in its core-shaking quality. This door opens up to a world of art that invites me on a journey beyond words where all that matters are emotions and sensations. Spontaneous, radical and raw. A quiet universe of sounds, a void where everything happens at the same time. Nestled here, between large canvases by Gerhard Richter and Roy Lichtenstein, I come face to face with Jackson Pollock’s masterpiece Number 32 from 1950: Fireworks of dark varnish on unprimed canvas, mounted onto a virginal white wall, dominating in its compositional reticence, restrained in its technical audacity.

Jackson Pollock, Number 32, 1950, laquer paint on canvas, 269,0 x 457,5 cm, K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany

Since 1964, Dusseldorf has been home to this Hauptwerk by Pollock (1912-1956), yet its birthplace was a barn in the woods of Long Island, New York City’s offshore isle on the east coast of the United States, pointing eastward into the Atlantic Ocean. In November of 1945, with financial support of art patron Peggy Guggenheim, Pollock and his artist-wife Lee Krasner bought a farm property on Accobonac Creek in the hamlet of Springs. A mere two-hour drive outside the urban jungle that was and still is Manhattan they found their artistic home amid the cedar swamps and salt marshes of East Hampton.

A typical 19th century farmers’ house, a simple wooden structure with an adjacent barn and a group of smaller buildings rise out of a picturesque and refreshingly unspectacular landscape. In the distance, the view of the woods of Merrill Lake Sanctuary give way to the blue waters of Napeague Bay, gently flowing eastwards, straight to the Atlantic Ocean.

Krasner brought her white iron bench from her Manhattan apartment and put it on the front porch. Small sea shells and starfish were lovingly arranged on the bedroom shelves, large boulders were dramatically arranged in the backyard. The two artists wanted unobstructed vistas, so they had the barn moved out of the main line of sight. This way, it was so much easier to watch storms moving in from the Ocean across Long Island Sound.

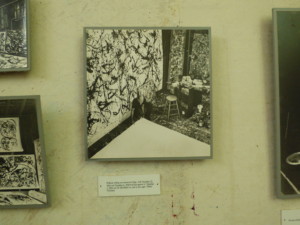

The small barn, originally used to store fishing equipment, was soon to become one of the most iconic artists’ studios in the world. First Jackson indulged in his artistic shenanigans, later, Lee let her creative juices flow. The two of them would leave the floors speckled, the walls sprinkled with their colorful genius. Pollock needed larger barn doors for his monumental canvases to fit through. And oversized windows – after all, that’s how the light gets in. A working heater and artificial light were secondary. What mattered was art and art alone.

Soon, cans of Devoe’s house paint and enamels found their new home on the studio shelves amid brushes of all shapes and forms in empty coffee cans, in mason jars, spilling over old cigarette boxes. In this backcountry of the swanky Hamptons, while wealthy New Yorkers escaped the City’s summer heat to dine on shrimp cocktails and watch the sunset over Sandy Hook Bay, art history was made, epitomized by Number 32.

Pollock, marinated in alcohol and jazz, used paint brushes, sticks and basters to apply color onto huge canvases stretched out on the floor. Spraying, dripping, dabbing, dribbling, pouring, Pollock altered between states of controlled creation and unleashed ritual ecstasy. The shaman of a new American art in a feverish trance danced around his canvas taking us on a soul journey into his spiritual realm, obsessed with creation and with creating. A demiurg from whose cavernous subconscious emerged drip painting, action painting and ultimately a new, revolutionary style that would leave its mark on the history of art forever: Abstract Expressionism.

Nowadays, in our age of ubiquitous floods of images, we like to think that we understand his style, this technique of drips and splats, the artistic ramblings of a mad man with a brush and a can of varnish. But do we? Art history proves over and over again that there is no replicating Pollock. His work has never lost its appeal and continues to fascinate art scholars and aficionados alike. The attempts at copying, at imitating Pollock in his approach to material and formal language are too numerous to count, yet none ever matched the emotional relationship a viewer enters into with a work by the master himself.

Titles of jazz songs or minimalist numbering mark his oeuvre. Pollock omits all sense of guiding our imagination by way of his titles. In Number 32 – as in so many cases – he does us a great favor. We find ourselves liberated from predetermined intellectual paths. Our synapses may fire according to their own free will, according to our own free associations. We are the masters of what we see, without any substantive bias. Pollock made sure of it. But what are we really seeing – here, between and beyond the paint?

On a monumental scale of almost three by five meters, entire universes open up in monochrome composition. Splashes of black and anthracite, shades of slate and coal exploding like fabulous stellar constellations across the raw beige canvas, rolling and unrolling, coiling and emerging, forming and fading, mimicking the courses of planets in eclipses and spirals. Stars collide, meander through space, rehearse the Big Bang. Creation in eruptions, sparks and lightning. And the cosmos is about us: Orgiastic specks in the shape of genitals, of pulsating organs, of blood spots, of actual coffee stains. Jackson, my friend! The fuel of life spilled over onto the canvas.

And it becomes evident that one of Pollock’s life bloods was jazz. In wild improvisation and gently flowing groove, sonic patterns and rhythms dance across the surface. Dynamic auditory accents, oscillating between gentle diminuendo and feverish crescendo in gray, in which the application of color reflects the intensity of sound. In highly energetic interaction with his material, Pollock masterfully captures feelings of movement, rhythmically as manifold as his entire composition is decentralized, without focus everything is of equal importance.

With tools that never touch the painting’s surface, the spontaneity of the composition, the dynamics of the creative process echo the artist’s inner turmoil. With a visual vocabulary that forms a jazz melody of rhythmic details, overlaid by improvisation, the work emerges from the interplay of its singular elements, both on the canvas and beyond. An artistic stream of consciousness that stirs something in our soul, reverberates, resonates, finally tears us along, and at the same time invites us to pause for just one moment to contemplate the vast void of the universe and our tiny place within this unimaginable structure.

Barely able to turn away from Number 32, it momentarily feels utterly impossible to return from this cosmos to the usual world, much less the world of conceptual art. As well worth seeing a special exhibition on contemporary art at K20 may be, it is this work of an eccentric alcoholic that always makes the visit worthwhile. It is the one piece that we should all and always and repeatedly lose ourselves in. Be it on a sunny Friday afternoon in June or in October in the Railroad Earth.

Usage Note:

The author gives permission to use extended quotation from the text material. In case of citation, the original source must be given in full. Any further use of this content requires prior written approval from the creator.